Denizen (/ˈdɛnɪz(ə)n/) – noun: a person, animal, or plant that lives or is found in a particular place.

On Suffolk’s wild Heritage Coast, just upriver from the mouth of the River Ore is a tidal tributary that in the scheme of things looks remarkably unremarkable, insomuch as the inherent beauty of the landscape, the vast, looming skies, the hiss of the tide and the call of the oystercatcher [and avocet ;-] are common to many of the inlets and creeks that populate this low lying and marshy coastal region.

Butley Creek, however, named after the eponymous river, and just-inland village, plays host to a thriving and traditional East Anglian profession, carried out in time-honoured fashion by the Pinney family, who have plied their trade from this notable little haven since Richard (their founding father) came to reside at ‘Ferry Cottage’ in the latter stages of the Second World War, having endured years of ‘privations and air-raids‘ (Pinney R- Smoked Salmon and Oysters) in the capital and yearned for some peace and quiet.

With rationing and food shortages a harsh reality of anyone’s existence then, supplementary protein was always sought and Richard, ever the entrepreneur, tapped into a ready supply of local rabbit, herring and terns’ eggs from nearby Havergate Island, which were duly harvested and distributed to the local populace and beyond.

Whilst Richard learned the craft of a Suffolk fisherman and the skills and techniques employed to catch not only herring, but cod, skate and soles, he soon discovered that whilst towing his beam trawl in the creek, he happened on occasion, to dredge up oysters, bygone relics of a once thriving fishery there, but now the surviving remnants of a forgotten commercial operation.

He seized upon the chance to reinstate the oyster beds, only to be informed by the Ministry Of Agriculture and Fisheries that ‘restocking the river would be out of the question’ requiring investment in imported oyster seed, for which there was no government funding available.

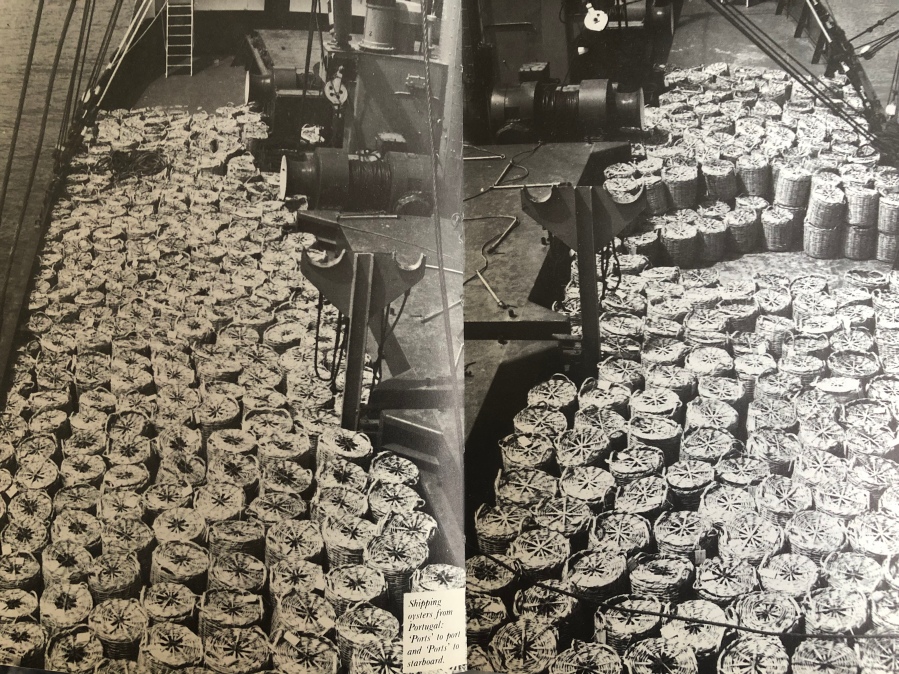

However, spurred on by ‘bacon and oyster breakfasts’ at the Crown and Castle Inn at nearby Orford, Richard resolved to restore the fishery and thus the town’s reputation as an oyster-producing port. Following several educational trips to Portugal to learn about the rock oyster, (which could be made available at all times of the year, unlike the more seasonal natives), Richard managed to eventually import enough Portuguese stock (120 tons in one consignment), to initiate the fishery in Butley creek, thereby ensuring its commercial viability and the re-establishment of an iconic local heritage.

That was way back in the 1950’s and Richard’s legacy endures under the keen and diligent stewardship of his son Bill, who now presides over not just one of the most well known UK oyster fisheries, but a group of local businesses that encompass smoking, commercial fishing, fishmongering, a restaurant and a wholesale business that has over time, put the Pinneys of Orford brand firmly on the country’s seafood map.

Now, as you’ll know and only too well if you follow me, that I love an oyster. In fact that’s a bit of an understatement, I adore them and make it my mission to sample local specimens wherever I travel. It never used to be that way though and I’m no expert and my shucking skills…..well let’s put it this way, many an oysterman’s eyes have gazed skyward when observing my rather cack-handed attempts at prying the delicious meat from its encrusted abode (although I am getting better!) It’s just that the more I consume the more I become fond of them and their provenance and variety, I find fascinating.

So on a mesmerisingly fine and tranquil morning last autumn, I made my way down the long, sandy and lonely track that bisects the estate of Gedgrave Hall and the glistening marshes of Orford down to the ‘Ferry’, where coastal travellers have, for centuries, ably forded the Butley River on their journeys North and South. It’s a breathtakingly beautiful part of our county and I always consider myself as having the best fortune to live with easy reach of such scapes, where land meets sea in a captivatingly seamless world of huge skies, distant sea and gently rolling topography.

I’ve known Bill quite a while. He was one of my first interviewees when I started writing back whenever and like most unassuming fishermen characters, he’s a ready oracle of marine knowledge for those wishing to learn more of his time-honoured profession. He’s also another one of those people you meet whose passion is not just noteworthy, it underpins their every move and seldom have I encountered such a raison d’être.

As we met that morning by his sheds at the Ferry, bathed in the gentlest of October sunlight and with not the slightest zephyr of breeze to disturb the river, Bill proceeded to imbue me with the whole nature of the process. Luckily for me that morning, some of the younger stock needed grading so I eagerly clambered about the very flat bottomed vessel they use for oyster-work and no soon than the outboard had coughed into life and revved a little, we were out in the middle of the river and amongst his crop.

Oysters here are basically grown from seed, sown traditionally and distributed evenly in areas upon the river bed and then dredged (by towing a small toothed rake/trawl) back up to the surface at about a year old and graded by hand, the undersized specimens being returned to their patch to grow on some more.

Bill grows Pacific Oysters (Crassotera gigas) and sources his seed from around the UK including the Channels Isles. There are two genetic variants ‘diploid’ and ‘triploid,’ diploids being the more conventionally sexually reproductive type and triploids being basically ‘sexless’ meaning they have an extra set of chromosomes, do not reproduce themselves, grow faster (theoretically) have larger meats and can be harvested to a quality standard all year round and exhibit superior disease tolerance.

Rather than sowing seed or young oysters directly into the river though, Pinney’s operation requires them first, to be placed first into mesh bags, which are attached to a floating pontoon, are easily accessible and where they remain for about three months. The process is all relatively simple. The young oysters grow on in the bags incredibly quickly in the fertile Butley Creek environment, filtering a ready supply of nutrients from the waters that ebb and flow through their shells.

As they ‘bulk up’ to about 15-20 grams in weight, Bill and his team size and thin them out over the summer months allowing them more space and less competition. After several gradings and when they have reached the required size, they are deemed ready to look after themselves on the river bed and are distributed in specific areas to grow on perfectly naturally to an ideal market weight of approximately 70 grams. This process takes anything from 6-12 months depending on the conditions, climate and of course their genetic makeup.

Having watched Bill fastidiuosly sort the young crop and transfer them to more spacious accommodation, it struck me that this whole artisan process is being repeated at farms all around the UK, each with its own distinct qualities, that distinguish it from its competitors. Oyster provenance is a whole different story and one that merits far greater research, but the concept of flavour and texture dependent on the terroir or in this case ‘merroir‘ is fascinating and like the world of fine wines, only really appreciable by a connoisseur.

Such a fascinating morning and a welcome insight into a sector of aquaculture that has as much relevance today as when the founding oystermen of the UK first began production.

On going ashore, Bill still had one thing left that he wanted to show me. We made our way to his walk-in freezer where, amongst frozen salmon, long-line bait and other sundries, were several boxes of the most colossal oysters I’d ever set eyes on.

‘These’, explained Bill ‘are our extra large oysters – the jumbos, which we dredge up in significant numbers, but because of their size we aren’t really able to sell in any quantity.’

With some of these gigantic gigas coming in at between 300-600g/each, not only do you get a huge bang for your buck, but a little more than a cursory slurp and of course not to everyones liking au naturel, with such a large mouthful.

Bill went on to inform me that these wonderful specimens, absolutely pristine in every respect, just like their smaller siblings, but just massively scaled-up, are often between 5-10 years old and form themselves into clusters or reefs that their relatively lightweight dredge can only pick off, a few at time. ‘The Chinese market love them and we do sell a few into that, but really there’s not much call for them.’ he adds.

‘We have to wait for a very low Spring tide, then they’ll appear at low water and we can get out to them and pry them away from each other.’ I’m simply fascinated, as to me, that particular practice seems like the ultimate in wild foraging.

And it got me thinking. As I thanked Bill enormously for his time and made my way home with a dozen Butley Creek ‘giants’ in the back of my truck, I couldn’t help but fantasise that there could be a new and untapped market for this delicious, nutritious and historically poor-man’s protein, if I could galvanise enough support and and impress the right people. As it turned out, I wouldn’t have to wait very long.

A few weeks later I strode into Wright Brothers Spitalfields restaurant – the oyster Mecca of the East End of London. I’ve eaten there many times and boy do they know their oysters, but nothing had prepared me for the afternoon that I spent with Exec Chef Richard Kirkwood and his team, as I produced a score of the larger oysters for their perusal, a wry smile on my face.

Chefs and FOH staff alike, crowded round to see these huge beasts. I’d not really thought too much about what we were going to do with them, but I wanted them cooked. Different ways and styles that showcased these beautiful creatures to the max and that brought a whole new meaning to oyster cuisine. In short I was hoping for something special. And I got it.

As we shucked away, prying open these huge crystalline edifices with varying degrees of success, Chef Kirkwood was already thinking on his feet about how to make the most of them.

First off was to confirm the flavour. Wright Bros are indeed aficionados having identified oysters, by founders Ben & Robin, as a way to Londoners’ hearts, opening their first bar in Borough Market back in 2005. So, having shucked three of the larger rocks, Exec Chef, Head Chef and Food Writer all quaffed and slurped them down with much applause, all unanimously agreeing that the flavour for such a huge piece of oyster meat was indeed exceptional. Long lasting and large.

On to the cooking. Smoking came first and four were duly dispatched below to the kitchen. Ceviche was proffered as well as tempura, fried in crispy Panko crumbs and an authentic Rockefeller. Dish after dish came back to us for sampling, as regular customers looked on, somewhat bemused by the excited and excitable oyster enthusiasts behind the bar, quaffing, chewing, savouring, comparing.

As the pile of giant shells dwindled and I sunk my teeth into yet another oyster, this time sautéed in a beurre noisette and dressed with green Tabasco sauce, I’d been struck by the simplicity and succulence earlier of the Tempura. It’s oh-so-light crunch harbouring a just-cooked oyster, still full of ozonous bite, luscious liquor, and a long sweet developing taste.

We continued, eagerly savouring freshly-shucked raw fish, which produced the odd gasp of astonishment from our onlookers, as oyster meats the size of fried eggs slid their way down, accompanied by thoughtful chewing, nods of agreement and the hugest of smiles as the flavours of saline, sweet and mineral developed and waxed and waned as with a fine wine.

We were down to our last two beauties. Head Chef Mike had wanted to ceviche them, but Richard and I had other ideas.

‘Just supposing,’ I ventured, ‘we were to make a play on a traditional favourite and rather than Tempura will did them in beer batter and served them with chips ?’

‘Oysters & chips….’ mulled the Exec Chef thoughtfully, his eyebrows arching inquisitively, although he didn’t think for too long and very soon two individual plates of perfectly crisp, golden battered oysters appeared, complete with the necessary accoutrements of chips, mushy peas and tartare sauce.

A triumph from the Spitalfields kitchen. Possibly a whole new and iconic East End dish that could draw on the history of London’s oyster-eating culture, whilst satisfying the appetites and desires of 21st century patrons and bringing a whole new meaning to the concept of fish and chips. And perhaps, the XXL Oyster Challenge…..you never know!

Watch this space…….

#oysterrevolution

If you don’t take me with you next time, our friendship is over. 😀 What a fabulous day! I’d love to try those whoppers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Linda if you’re anywhere near Fram this weekend there’s a half dozen XXL’s for you here x 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh I wish! That’s so kind, thank you, but I have a mountain of cooking to do this weekend and I’m tethered to the stove. Perhaps another time? xxx

LikeLike